We all know it but someone has to say it: zombies are the new vampires.

Vampires had a lovely sort of fin-de-siècle decadence about them that perfectly suited the mood of the late 20th century. Rising gas prices, the resurgence of Christian fundamentalism, neo-liberal pundits running the world markets into the ground with all of their dot-com bullshit about a “weightless economy,” 9/11 looming on the horizon, boy bands … the party was coming to an end, and, deep down inside, everyone knew it. So why not emulate the monster most likely to eat the other guests (and do so with a modicum of style, at that)?

Style exacts a stiff price, though, even among the undead. Pancake makeup takes a long-ass time to apply smoothly, and all of that black leather, velvet and lace is expensive, heavy and difficult to launder. This is the real reason that the only people interested in dating vampires and their gloomy kissing cousins, the goths, were other vampires and goths: vampires are the ultimate in high-maintenance girlfriends. By the time the beautiful and spooky actually finish dressing and are ready for a night on the town, most of us are pretty much looking for breakfast.

Enter the zombie: the ultimate low-maintenance monster. Crumbling, shambling, moaning, driven only by the neverending search for more brains to consume, the zombie has become the cultural mascot of the early 21st century.

Why? I think it has a lot to do with the failure of our collective longing for transcendence to actually pay off in any sort of immediate and gratifying way. Vampires were symptomatic of a massive cultural delusion that it was possible to escape the inevitable aging and crumbling of the flesh, to be young and beautiful forever. Cyberpunk fantasies about escaping the meat by uploading one’s consciousness into the antiseptic infinity of cyberspace were just a chrome-dipped retelling of the same old story.

Zombies, though, are a walking (okay, shuffling) reminder of the inescapability of decay. You can try to break the shackles of the physical, to rise above the meat all you want, but your mindless, rotting body will catch up with you eventually. This is the horror of the slow zombie: it never ceases to remind you that at some point, you will tire, and it will not. And then, of course, you’re fucked.

*

I spent a lot of time (too much time) last year mulling over the problem of fast zombies, when I could have been thinking about other important matters, like, um, the environment. With the introduction of horror video games and their movie spinoffs (Resident Evil being a case in point), all of a sudden, zombies came in two flavours, and the first question that you as a viewer had to ask yourself when renting a new zombie movie was, what kind of zombie were you dealing with? Fast, slow, or, worst of all, the dialectical resolution of the two — zombies that *seem* slow until you let your guard down and they actually turn out to be fast?

My working theory is that fast zombies are actually a kind of hybrid: equal parts zombie and Frankensteinian flesh re-animated with the aid of the very technology that confounds and frightens us on a regular basis. The zombie Dobermans from Resident Evil are a case in point: if you missed the news, evil US Army biology nerds have actually been able to make those since 2005. Take a puppy that’s been dead less than three hours, pump it full of ice-cold salt solution, then give it a blood transfusion and a little electro-shock, and you’ve got a zombie Frankendog that is fully capable of chasing Milla Jovovich in her little red minidress across the empty post-apocalyptic landscape (it should not surprise anyone that the empty post-apocalyptic landscape is, inevitably, Toronto).

The loveable video-game playing zombie chained in the shed at the end of Shaun of the Dead is the closest thing that I’ve seen to a domestication of the fast zombie. If your XBox skills are so poor that you need to have a zombie n00b as a punching bag, your sorry ass deserves to be eaten.

*

Zombies are, by their very nature, parodic. And yet all too often, businesses and cultural institutions seem to think that they can simply guarantee their own hipness by dropping a zombie or two into their product line without stopping to consider the unsavoury connotations that associating themselves with the living dead might create.

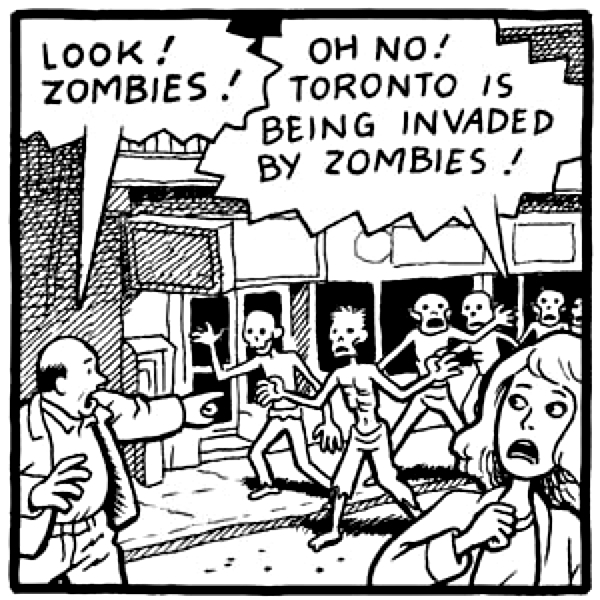

In the latest in a series of what can only be described as spectacularly bad advertising campaign decisions, the City of Toronto’s Live with Culture program has commissioned indie cartoonist Chester Brown to draw a series of strips about a lonely zombie who actually appreciates going to art galleries, bookstores and movies more than eating brains. You can get the whole thing on the City of Toronto’s website as a webcomic.

It’s pretty great, crammed full of all sorts of nasty in-jokes. In one episode, the zombie and his girlfriend go to the Royal for a screening of Bruce McDonald’s never-completed adaptation of Brown’s Yummy Fur (Ed the Happy Clown). Onscreen, the characters are alluding to the fact that Ronald Reagan’s head has been grafted to the end of Ed the Happy Clown’s penis … which is actually kind of awesome, when you consider that three separate levels of government have just paid for you to see that.

A little more problematic is the fact that this selfsame advertising campaign positions you, the citizen “living” (even “living dead”) with culture, as a damned soulless corpse whose only possible redemption lies in the wonderful events and artifacts that our various government granting bodies choose, in their beneficence, to fund. Really, though, they’re just being honest: as I mentioned at the start of this messy little series of meditations, our monsters are us.

Besides, if I have to choose between whether my tax dollars go toward the creation of spiteful, insulting little funnybook narratives that infer that I’m some sort of ghoulish parody of a human being, or yet another magic realist novel about mother-daughter relationships and the painful wisdom of growing old, I’ll take the zombies every time, thanks.

First published as “Alienated 9: Zombie Parables.” Matrix 79 (spring 2008): 52-53.