On January 9, 2009, Mercer Union launched “Street Poets & Visionaries: Selections from the UbuWeb Collection” to a packed house. The text that I wrote for the catalogue of this collection of found poetry follows, as does a link to a Flickr set of images of the event.

The quality of mind in the radio telescope is its will to select.

— Christopher Dewdney, “Parasite Maintenance” {{1}}

What are the outer limits of appropriation?

Digital culture is obsessed with this question, from both an aesthetic and a legal perspective. On the one hand is an entire century of artistic practices that gleefully encourage the copying and recirculation of cultural materials, from Delta blues and Dada to Flarf and mashups. On the other hand is an increasingly restrictive legal climate, which, as Siva Vaidhyanathan has argued at length, is entirely incapable of dealing effectively with “emerging communication technologies, techniques and aesthetics” {{2}}.

One response to this deadlock between the aesthetics of appropriation in a digital milieu and the legal forces that would constrain them is an increase in bandwidth. In his ABC of Reading, Ezra Pound claims that “artists are the antennae of the race” {{3}}, but in a digital milieu, a set of rabbit ears will no longer suffice. For Christopher Dewdney, contemporary artistic sensibility is analogous to the functioning of a satellite dish. From such a perspective, artists are devices for the accumulation and concentration of data, cool and dispassionate. The quality of the objects and texts that they produce depends on “the will to select.” Thus, the individual’s ability to sort and process the ambient signals that constantly bombard all of us is what constitutes contemporary criteria for a successful artistic career.

As Craig Dworkin has noted elsewhere, self-declared “Word Processor” Kenneth Goldsmith‘s personal oeuvre falls squarely into this tradition of technologized, high-volume appropriation {{4}}. This is especially true of recent works such as Day and the American trilogy (The Weather, Traffic and Sports), all of which duplicate huge swaths of copyrighted texts and performances with studied Warholian indifference. In this context, even Goldsmith’s curatorial work on the decade-old UbuWeb, the world’s largest digital archive of avant-garde sound recordings, concrete poetry, video, outsider art and related critical materials, is arguably part of the practice of appropriation art — perhaps even Goldsmith’s greatest work.

Goldsmith normally proceeds by identifying a neglected (because mundane, or, in Goldsmith’s terms, “boring”) site of cultural discourse, such as an average edition of The New York Times (Day), or an entire weekend’s worth of radio traffic reports (Traffic). He then transcribes that discourse meticulously, reconfigures the resulting digital manuscript as a book, and attaches his name to it. Though such projects have been common in the art world since the heyday of Conceptualism, they are relatively new in the world of poetry. By porting an established practice for aesthetic production from one field of cultural endeavour (gallery art) to another (poetry), Goldsmith has simultaneously constructed himself a career and staged an intervention which has changed the stakes of contemporary writing.

And yet. The texts and objects in “Street Poets & Visionaries: Selections from the UbuWeb Collection” occupy a privileged position, one that at first glance seems utterly counterintuitive in the context of the rest of Goldsmith’s oeuvre. The digitized versions of this material used to appear on UbuWeb under the heading “Found + Insane”; Goldsmith’s text on the website notes that “we’ve redesigned and renamed it Outsiders, reflecting broader cultural trends toward the legitimization of Outsider work,” reflecting a remarkable degree of cultural sensitivity from someone whose public persona is often gleefully abrasive and provocative {{5}}. Moreover, when exhibiting this work, Goldsmith never directly attaches his name to it, preferring the relative anonymity of “UbuWeb” and the curatorial first-person plural.

The greatest difference between these materials and all of Goldsmith’s recent work is that he circulates them without “denuding” them — this is Goldsmith’s term for the process of stripping away “the normative external signifiers that tend to give as much meaning to an artwork as the contents of the artwork

itself,” such as font size, lineation, accompanying illustrations, and so on {{6}}. In gallery shows such as this one, the original objects themselves are displayed, even though for Goldsmith, the normal practice would be to discard originals after digitization like so many empt}}y husks.

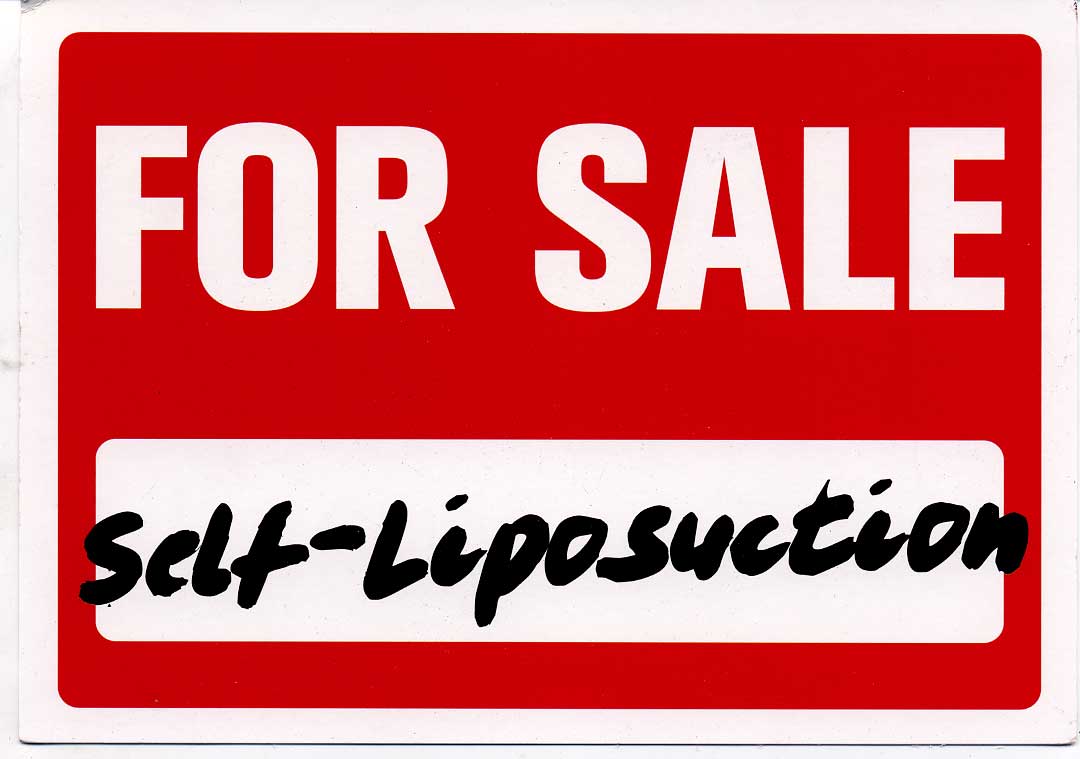

Part of the value of these objects is their stubborn materiality. Yes, the content itself is important, and Goldsmith sometimes performs these works as part of his own undifferentiated output, but there is also something here that resolutely resists digitization: the crackle of ancient Letraset, photocopier noise, fragments of yellowing Scotch tape, the trace of a hand wielding a Sharpie. These works, I would argue, are the secret truth of Kenneth Goldsmith’s practice: something small and sacred that makes his great, sprawling, transformative profanities possible.

[[1]] Dewdney, Christopher. “Parasite Maintenance.” Alter Sublime. Toronto, Coach House Press, 1980. 73-92.[[1]]

[[2]] Vaidhyanathan, Siva. Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual Property and How It Threatens Creativity. New York: New York University Press, 2001. 133.[[2]]

[[3]] Pound, Ezra. ABC of Reading. New York: New Directions, 1960. 73.[[3]]

[[4]] Dworkin, Craig. “The Imaginary Solution.” Contemporary Literature XLVIII.1: 29-60. 34.[[4]]

[[5]]Goldsmith, Kenneth. “Outsiders.”

[[6]]Goldsmith, Kenneth. “The Bride Stripped Bare: Nude Media and The Dematerialization of Tony Curtis.”