At the end of the 20th century, I was writing and publishing a lot of books about the Internet. (Everybody has to pay the rent somehow.) Some parts of these books still hold up reasonably well; others are misguided and flat-out wrong in ways that make me wince openly. But that’s the way it is with things you wrote nearly a dozen years ago. The rights to both books reverted to Mark and me several years ago, so they are now available as PDFs.

CommonSpace, an Internet theory book I co-authored with Mark Surman, is interesting because we were searching for a term for what we now call social media — various technologies that allowed people to write back to the Web, which was, for the most part, static in those days. At some point I’m going to write a “CommonSpace Revisited” essay and flag the useful bits and the parts about which I’m more ambivalent, but what strikes me when I reread it is how much fun we had when we were writing it. Parts of it are still pretty funny, but there’s a lot here that’s of historical interest too. It may be hard to imagine now, but there was a time when it was possible for the official slug line of Blogger to read “Amphetamines for Your Website.”

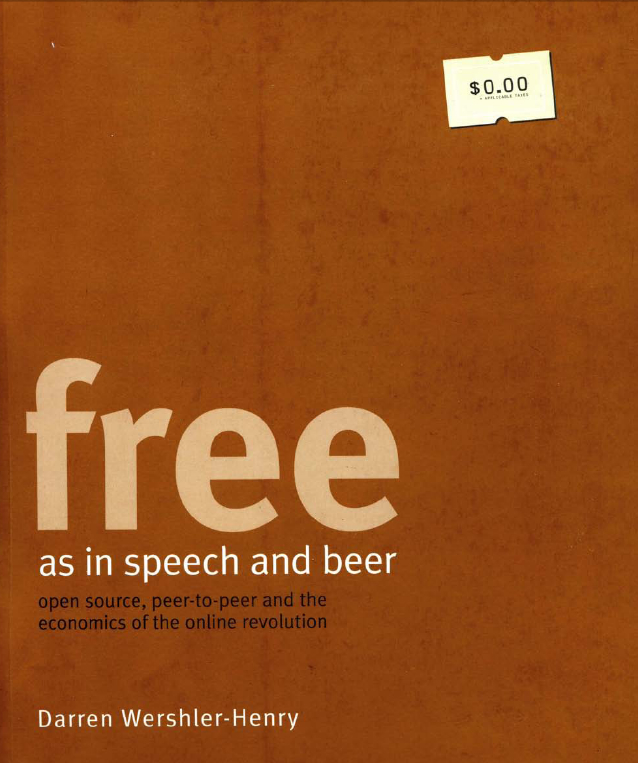

FREE as in speech and beer, which came out a couple of years later, holds up a little better. It’s mostly an intellectual history of the notion of freedom as it pertains to sharing on the Internet. The book outlines the difference between “free as in rights and liberties” of Richard Stallman and company, and the “free as in getting something for nothing” that still drives file-sharing today, and contextualizes them in terms of the theory of potlatch and the general economy. Again, it was a lot of fun to write, and it may be of use to those too young to remember that Napster really wasn’t invented by Justin Timberlake. In retrospect, though, the tone bothers me, and I avoided the probable conclusion in favour of a kind of techno-optimism, which, given the way social media has developed, I deeply regret. So there’s revision to do here as well.